Opportunities through Education

By Max Esterhuizen

During her first unofficial college visit, Dickenson County native Rachel Moore looked up and saw the sprawling, Gothic architecture that surrounded her.

As she stepped off the bus, a giant banner festooned across the architecture showcased the spirit of Blacksburg. “LET’S GO HOKIES” was draped across the famous Hokie Stone.

“I took a picture of it,” said Moore, a freshman in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and a longtime 4-H’er. “When I saw that sign, something clicked in my head.”

Her first experience of Virginia Tech’s Blacksburg campus was made possible by the College Access Collaborative, a program at Virginia Tech that increases academic preparation, access, and affordability for first-generation, low-income, underrepresented minorities, women, and students from rural and inner-city communities.

“Educated communities are stronger communities,” said Karen Eley Sanders, the associate vice provost for College Access. “Higher levels of education are correlated with better health, lower unemployment rates, and civic engagement. Educational attainment is a proven strategy to lift individuals and families out of poverty. Education literally pays, transforms lives, and uplifts communities.”

It’s a program that’s proven extremely valuable for 4-H and Virginia Cooperative Extension agents across the commonwealth, including Dickenson County agent Kelly Rose ’17, who has used it to organize trips to Virginia Tech. The trips are an experience youth in the rural county would not otherwise have.

“I feel very strongly about giving kids in far southwest Virginia the opportunities that their peers have in other parts of the state,” Rose said. “A lot of the time, one of the barriers is just getting the kids on campus. Many are geographically isolated and have limited means. A lot of the kids here don’t get to travel outside of the area and taking them on a trip where they can see what a college campus looks like is invaluable.”

The Science Festival, held annually on Virginia Tech’s Blacksburg campus, is one of the tools utilized by the College Access Collaborative and by Rose, which helps students have the same opportunities as others in the commonwealth.

“If they have never stepped foot on a college campus before, it’s hard for them to envision themselves at college,” Rose said.

Being geographically isolated is a challenge for the youth and agents of far southwest Virginia. For example, it takes about three hours to get to Virginia Tech’s Blacksburg campus from Dickenson County. And to Richmond? That’s at least a six-hour trip.

And that’s the purpose of the College Access Collaborative Program – to bridge those distances and remove hurdles to allow youth such as Moore the opportunity to experience a college campus.

Moore was involved with 4-H in her county for years with her father. Rose spoke with both Moore and her father and mentioned that trip to the Science Festival at Virginia Tech.

“Kelly said that we could enjoy the exhibits with our parents because they could be chaperones, walk around with you, and basically get a free tour of the campus,” Moore said. “I’m really into science, so it was a win-win. When it came time to choose a college, familiarity was a big factor for me. I had a great experience on the trip and it was a deciding factor for me.”

What helped Moore make college more affordable is a platform called RaiseMe, a program that helps high school students earn scholarships starting in ninth grade. These scholarships – called “micro-scholarships” – are earned for various achievements, from earning an “A” to community service and other extracurricular activities. With Virginia Tech as a partner institution, Moore took advantage.

Every “A” and activity added up, and Moore earned more than $9,000 toward tuition through the platform.

“It financially freed me up,” she said. “Every dollar was less of a financial burden for me.”

The impact of the College Access Collaborative can be felt across the commonwealth.

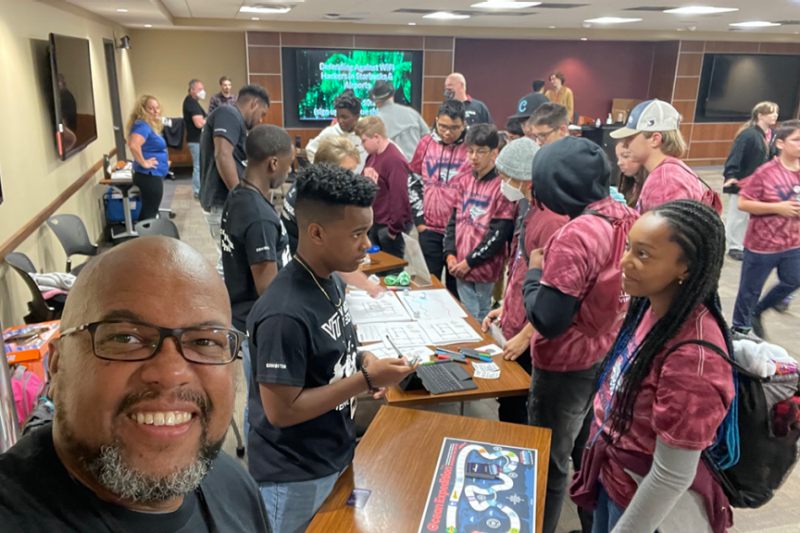

Henry County, has used the opportunities provided by the College Access Collaborative for years, including attending the Science Festival. But a new tool Hairston found this year was Junior MANRRS (Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources and Related Sciences), an organization that helps students interested in an exciting future in science, technology, engineering, agriculture, mathematics, or related careers.

“The College Access Collaborative has been an incredible partner in our mission to provide a diverse array of resources to the youth who need it most,” Hairston said. “The program has given us the ability to transform lives and give opportunities to those who otherwise might not have had them.”

Hairston utilized Junior MANRRS and even had an intern to help develop localized programming from the ground up.

Jillie Wilkins, Hairston’s intern, developed an escape room where students had to use different clues to move to the next station and ultimately leave the room by using reading and math skills – as well as collaboration with each other.

“I thought that the escape room would be an interesting activity for students to complete and it would feel like a game instead of just work, but it would also challenge them to think,” Wilkins said.

Wilkins was involved with 4-H in her county “as long as she could remember.”

“I thought this would be a great opportunity for me to see the different students in our community and be able to work with them on different skills,” she said. “I think that I gained a deeper understanding of what students enjoy and how we really are the people they look up to and to them our opinion or advice matters.”

Wilkins used the skills she gained and harnessed her passion for young minds to become a teacher at Stanleytown Elementary, where she works with Hairston to bring 4-H programming to her classes.